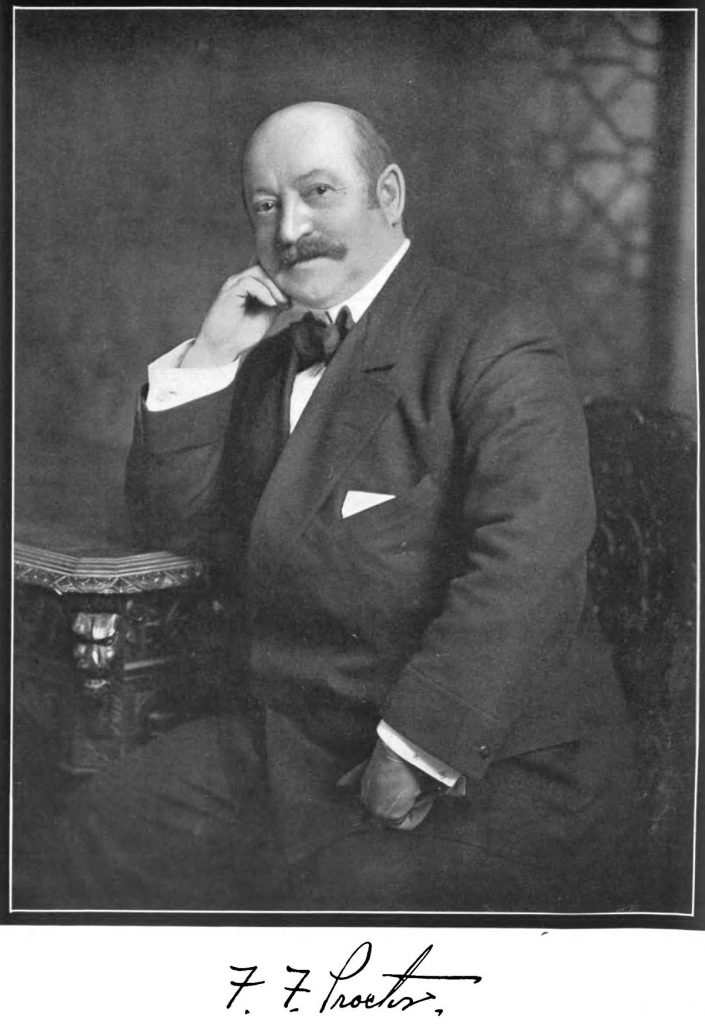

Who was F.F. Proctor?

Frederick Freeman Proctor was a performer before he was a presenter. A rare, quirky bird, Proctor was an equilibrist—a master of balancing feats—billing himself as “The Great Levantine.” Basically, as a young man in Boston, he took a 19th century obsession with physical fitness and turned it into a road gig spinning barrels and juggling pins.

Born in Maine in 1851, F.F., as he would become known, was not exactly a star, but he made a living. He realized that, in those halcyon days of vaudeville, he could put his mental skills to better use than his physical ones. He began balancing receipts rather than barrels.

The journey to becoming the “Dean of Vaudeville,” owning and operating over 50 theatres from Maine to Delaware, began with the purchase of the Gaiety on Albany’s notorious Green Street. He and his wife sold tickets, made popcorn and cleaned the floors.

Long before he could afford to build Proctoria, his expansive Woodbury manse, in 1912, he lived in humble digs in Nassau, in southern Rensselaer County.

Proctor, who insisted on wholesome fare, leased one hall after another, building a kingdom in New York City, and eventually up and down the coast. His concept of continuous vaudeville, bracketing silent film screenings with live entertainment from the form’s heyday—everything from dancing teams and dog acts to operatic divas and, naturally, acrobats—was simple, yet brilliant.

His first bid in Schenectady, also in 1912, was a modest hall at the corner of State and Erie, bordering what, at that time, was still a canal rather than a street. It would later become the Erie and the Wedgeway before the mainstage became a parking lot and the original marquee a rented billboard.

When Proctor’s most stately theatre, our own Proctors on State Street, opened, it did so with a continuous bang. At Noon on Dec. 27, 1926, the first patrons paid 35 cents to see Bebe Daniels in the seven-reeler Stranded in Paris, as well as a never-ending stream of hoofers, yucksters and singers. Late in the evening, 7,000 admissions later, the show was still going (with late patrons paying a few pennies more).

But he built the Proctors we know. Recent renovations have returned the hallowed hall to its pristine opening night glory. When Stranded in Paris played, Proctors was one of almost two dozen theatres in downtown Schenectady. It’s the last man standing now.

F.F. Proctor, an arts and entertainment pioneer in so many ways, did not live to see movies undo his “empire.” He did not live to see multiplexes disrupt the great downtown palaces, or to see the internet pull on the thread of live entertainment.

He actually sold his “jewel” to RKO three years later, and stepped back from the footlights to enjoy the fruits of Proctoria (which was later purchased by West Point) until his death, a few months later, in Larchmont, in September 1929.

His legacy lives on in Proctors, and not just in the grand piece of Thomas Lamb-designed architecture that bears his name. Like its founder, Proctors has branched out, bringing—particularly through its robust education program and its work with Capital Repertory Theatre and Universal Preservation Hall—arts and culture to the entire Capital Region.